1st December. At a friend’s in Walthamstow, post fungi-hunting in Essex

‘When are you going to take me mushroom hunting then?’ If I had a penny for every time I’d been asked that question I’d have, well, about £1.50, I think. The trouble is, I am always ready to head out but when that rainy Sunday morning comes round, most folk are not as keen as they were in the pub the night before. Today was the exception, the sun was out and at 8 a.m. my over-enthusiastic friend was banging on the door and insisting I made good on my promise. The horrific task of driving in London becomes an absolute joy when no one else is on the road and just over an hour later we were standing in a woodland car park, most of the way to Cambridge, drinking tea and putting on our boots. I love the woods when they are like this, crisp underfoot, chilly on the breath but warm enough to not need a coat, and with that heady, late-autumn smell on the air. A forest clearing, a shabby lawn bordered by majestic oak trees, provided the ideal spot to hunt for the last of the season’s porcini mushrooms, but despite our search, none were to be found, most had fruited earlier in the year, and the temperature was now too cold for them to ‘come again’. As they say, that’s just how it goes.

We walked on, finding a patch of hedgehog mushrooms, pale orange, almost peach-coloured, nestled in the leaf litter. They grew in a wide banana-shaped arc on the forest floor, in the shadow of a huge beech, ‘mother tree’, probably 150 years old and obviously responsible for the numerous younger trees that surrounded it. They gave a good weight to our otherwise empty basket but the real pleasure came less from what we picked, more from the hunt and the opportunity to walk in the woods together. Half an hour later, on the border of the beech woods and a pine plantation, we realised that we were surrounded by winter chanterelle, so many mushrooms that they seemed to have crept up on us, not the other way round. Growing often in patches of many thousands, this wonderful little fungi has a cap that looks very much like the fallen foliage in which it flourishes, ‘hiding in plain sight’ summing up its appearance perfectly. Once flipped over, it reveals a long yellow stem, which gives it another of its common names, the yellow leg. Faced with such a prolific and tasty mushroom as this, no conversation was needed, just quiet, methodical picking, a perfect mix of calm and excitement until the basket was full and a spot of rain told us it was time to head home.

Quick pickled winter chanterelle with rice wine, chilli and garlic

Some winters I pick this amazing frost-resistant fungi when there is snow on the ground and even though I’d waited almost a year for them to come out so I could make this pickle, I can see no reason why it wouldn’t work equally well with all sorts of other mushrooms, although it won’t look quite as lovely. This is a great recipe, ready the day after you make it and perfect to bring a bit of zing to any winter plateful. It took six texts, four tweets, five emails and three requests in person before Rob, head chef at Clerkenwell’s Modern Pantry, generously gave up this most prized of culinary secrets.

40g peeled ginger julienne (thin-sliced, in other words), 5 finely sliced garlic cloves, 2 medium deseeded and finely sliced red chillies, 40g fresh green peppercorns (substitute capers if needed), 150ml extra virgin olive oil, 1kg winter chanterelle or similar, 100ml rice wine vinegar, 50ml soy sauce

Sauté the ginger, garlic, chilli and peppercorns in the oil until fragrantand soft. Add the mushrooms and fry for 2 minutes. Add the vinegar,soy and 50ml water and cook for another minute before removing from the heat. Leave for 24 hours to pickle/marinate before serving. This is a zesty Japanese-style ‘light’ pickle so I imagine it won’t last for months like a traditional preserve.

As a footnote, I’d always suggest dry-frying (without any oil) thewinter chanterelle for a minute beforehand, which will allow them to release some water, so when you do come to cook them they will fry rather than just poaching in their own juices. This liquid can be reserved and used to make a mushroom gravy. On their own winter chanterelle are delicious fried with brown (caramelized) butter and although they become tiny, they dry very well so can be used as an addition to soups and stews throughout the year.

3rd December. Hampstead Heath

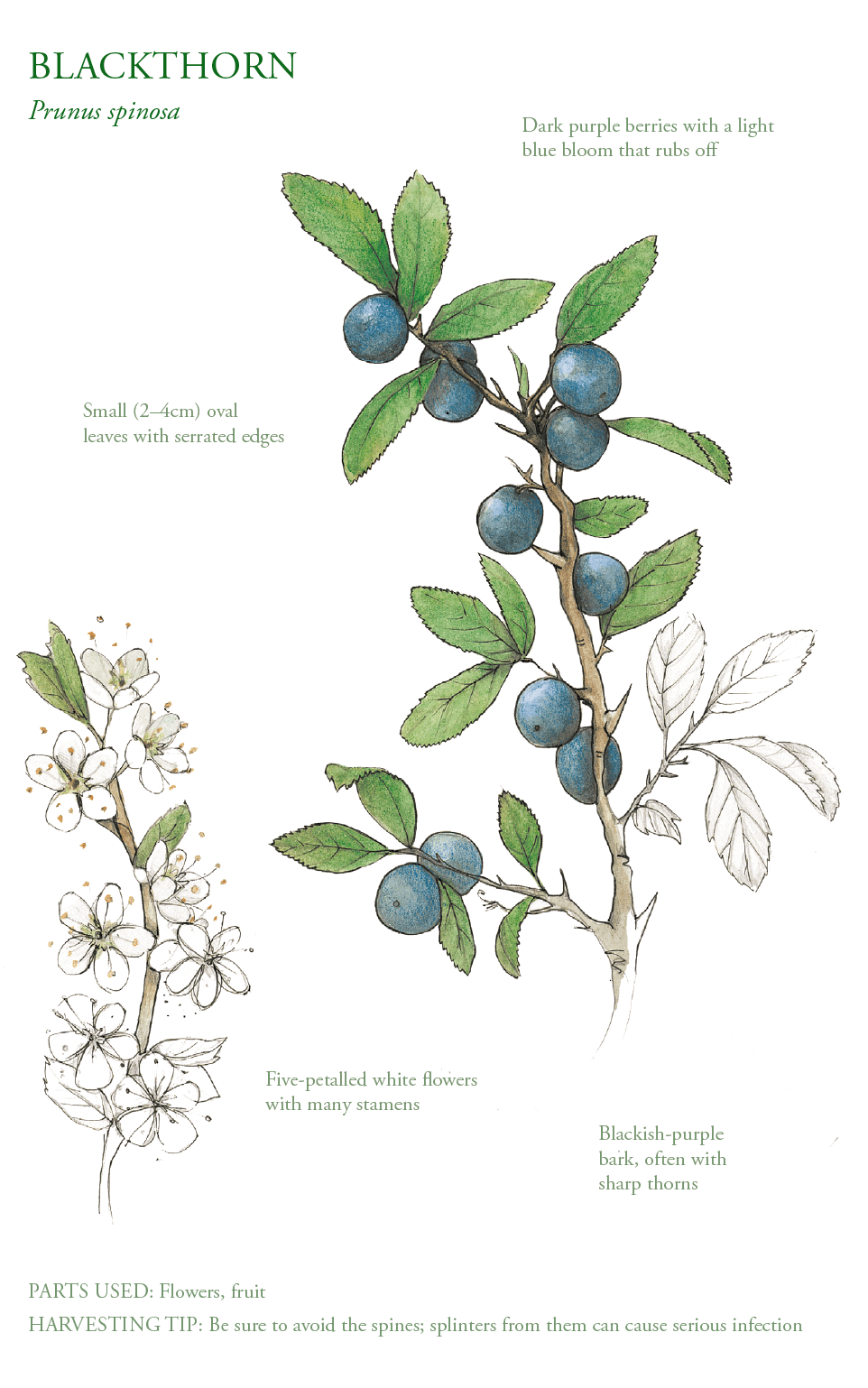

Accentuated by the utter absence of anyone else, which is unusual for this huge patch of London greenery, and the presence of a low-hanging mist floating just above the damp grassland, the oddest of sights greeted me today as I took a walk on ‘the heath’. It appeared to be more the result of witchcraft than any natural phenomenon. A hedge of blackthorn bushes, hundreds of metres long, naked and skeletal as one would expect right now, except that every 15 metres or so was a big patch of extremely late fruit, vastly exceeding its ‘fall-by’ date. Sloe is the more common name for blackthorn, and generally used when describing these small purple plums and the festive flavoured gin for which they are famous. The traditional time to harvest is much earlier in the year, when the first frost arrives, this deadline having the dual purpose of cracking the skins to help release flavour and also allowing the fruits as long as possible on the branch to make plenty of sugar. As anyone who has tasted raw sloes will tell you, even when fully ripened they are extremely drying, being very high in tart-tasting tannins. Finding myself at a loss as to the cause of this weird, wild alchemy, I collected what I could, already considering what this fortuitously late bounty should be used for. Sloe gin? No, too predictable. Sloe jam? No, it would just sit on the shelf with all the other random experimental preserves. Something with herbs and alcohol? Yes, that’s always a good option; some further research would be needed. I was surprised to find these sloes to be in excellent condition, fat and firm and apparently unconcerned that every other fruit had fallen to the ground a good month earlier. Nature is just so unpredictable, wonderful and confusing; very often I concede that my purpose is not to reason why it does what it does, but to just be in the right place at the right time and gratefully receive its gifts.

Blackthorn and elder pacharan with vanilla and coffee beans

1 litre ouzo, raki or Pernod, 1 litre vodka, 300g ripe sloes, 300g elderberries, 6–8 tbsp sugar, 2 cinnamon sticks, 24 coffee beans, 2 vanilla pods

I could have described this drink as a sloe pacharan, but I think blackthorn sounds more exotic. The recipe comes from the Basque region of Spain and is traditionally made with just sloes and any aniseed liqueur; ouzo, raki or Pernod will all do fine.

I used a litre of Turkish raki mixed with a litre of vodka (I’m such acheapskate). To this I added the ripe sloes and, finding myself with not enough fruit, supplemented them with the same amount of elderberries, picked and frozen earlier in the year. In a big glass jar, I left everything to infuse for a couple of weeks, allowing the alcohol to take on the wonderful colours and flavours of the fruit. At this stage I added the sugar, the cinnamon and two dozen coffee beans. An authentic pacharan would also include orange peel and chamomile flowers, but I opted for including a couple of vanilla pods, figuring the anise, vanilla, coffee combo would work well. Then the waiting begins. This needs to be left somewhere dark for at least a month, given a little shake every few days and then strained through muslin and bottled.

It will also work very well with just elderberries and although the flavour is delicious after only a month or two, a year later it will have adopted all manner of unusual herby notes and taste more like something made by a sixteenth-century monk than a modern-day forager. I have triedvarious other recipes with sloes – jams and jellies and even an unsuccessfulattempt to mimic Japanese sour plums – but this is far and away the best I have come across.

8th December. Brockwell Park

Today I found myself saying, ‘I can’t believe I’ve never been here before.’ This place read like a tick-list of all my favourite winter plants, or at least those that I find in the city: Michaelmas daisy, ox-eye daisy, yarrow, lucerne, mugwort, sow thistle, winter cress, feverfew, chickweed, self-heal, cat mint, nettle, vetch, sorrel, sweet violet, crow garlic, hedge mustard, hoary mustard, lavender, rosemary and dozens of others. Finally getting round to visiting an old friend who lives ‘south of the river’, I found myself in Brockwell Park, exploring its wilder corners, excited by its diversity and considering the concept of ‘shifting base-line syndrome’, an idea more commonly applied to ecology and natural evolution than to the social and physical changes of a city. Brixton has moved on enormously in the last few years, the dreaded and sanitising effect of what is often referred to as ‘gentrification’ has done its worst, or its best depending on your view; the edginess and the excitement has all gone and the coffee shops have arrived. Unlike much of London, our parks are something of a time warp; the signage and the food offerings may have been updated but not much else has changed. They are still the places we go to clear our heads or get some perspective, within but removed from the frenzy that surrounds them. For me, the park is a place where I can look at the bigger picture, with just enough distance to get a wider view.

Today the city looked like a huge body of water, shifting and flowing, constantly moving and always changing, and the park, obviously, was an island, offering a sense of stability and constancy, the purpose for which it was created and the role it still plays. Dragging myself away from my musings, I realised that my friend was waiting for me at his house and I was late. ‘Under the weather’ was how he’d described himself and I’d promised not only to keep him company but to bring him some fortifying wild plants. A nearby flower bed waved at me, literally (it was a windy day), so I grabbed a small bunch of three wonderfully aromaticwoody plants and headed off to my friend’s house to create a warming winter tonic.

Yarrow, lavender and rosemary oxymel

350ml cider vinegar, 225ml thin honey, a handful of yarrow stems and leaves, a handful of lavender leaves and flowers, a handful of rosemary leaves and stems

Vinegars have a long history of use as medicinal cordials, as well as for flavouring and preserving food, and vinegar drinks are having something of a renaissance at the moment, with posh cocktail bars favouring the sweet varieties known as shrubs, infused with fruits, berries or syrups. I love the ease of making vinegar-based drinks and home remedies and they are ideal for all manner of experimentation. Oxymel comes from the Latin oxymeli, meaning acid and honey, and traditionally this blend would have been used as a way to administer herbs that were too bitter or unpleasant to take on their own. Numerous recipes exist, many dating back thousands of years, with proportions and ingredients varying enormously, as do the herbs that can be included. This recipe, concocted for my poorly friend, uses only safe, edible plants, and although they have their own medicinal properties I was in no way pretending that I was a qualified herbalist, more that I wanted to give him a soothing winter tonic to help him feel a little better, much the same way as we use a ‘hot toddy’.

The reason for the proportions of cider vinegar and honey that I used was nothing more precise than that the vinegar came in a 350ml bottle and the honey in a 225ml jar, so feel free to play around and make your own version more or less sweet, thicker or more runny. I gently heated both together, just long enough for the honey to melt, then stirred in a chopped-up handful of yarrow stems and leaves, the lavender and rosemary. When it had cooled, I used a couple of tablespoons of the mix to make my friend a delicious tea and I put everything else into a sterilized jar, telling him to leave it there for a couple of weeks before straining out the plant matter. This, or any similar blend, can be taken daily as a tonic, used like a cough mixture when needed or drunk as the base of a herbal tea.

For an alternative use for these three herbs, consider using them ground in savoury muffins or wrapping them round any fatty meat that you are roasting; they all have their own slight bitterness, so will let your digestive system know it’s time to spring into action.

20th December. Alexandra Palace

If foraging teaches us anything, it’s to enjoy and celebrate what is available, not to hanker after what is not. If only I/we could carry this simple lesson out into every aspect of our existence, especially city life, where everything is demanded and supplied immediately and where choice is infinite and often unappreciated. In a rather less than Zen mindset, I left my house today in a horrid mood, having slightly taken out my computer-related frustrations on everyone I had had any contact with – to my shame, the delivery man who asked me to sign for a neighbour’s package getting the worst of it. After an hour or so of despatching various pre-Christmas chores, I headed to the enormous green hillside a couple of miles from my house, partly to forage, partly just for the view, but mostly because I knew that the walk to its summit would tire me out and thus render me less grumpy. Ally Pally, as it’s universally known, opened in 1873 as a public venue and was dubbed ‘The People’s Palace’. In 1936 it was the site of the BBC’s first-ever television broadcast and it still plays host to regular exhibitions and concerts, but although it’s relatively close to my house I seldom visit it except for the annual firework display. The palace grounds mostly consist of a huge south-facing hill with amazing views across the whole city and are made up of some wonderful, minimally managed, grasslands, meadow and woods; a real treasure for anyone who views the city’s open spaces as I do. Today, this close to Christmas, it was very cold and bitterly windy on the exposed hillside and it quite literally blew my bad mood away, leaving me clear headed and able to appreciate my surroundings.

I gathered the ingredients of a winter salad, a mixture of my favourite seasonal greens. First in the bag went some salad burnet, an unassuming little leaf that tastes like a wonderful cross between cucumber and melon. Hot on its heels, the peppery delights of hairy bittercress, growing in big tufts in the middle of a flower bed, one of the few more managed spots here. Next I collected some white dead nettle, with both its leaves and flowers on show, followed by the greeny purple leaves of some young garlic mustard and a small but succulent patch of chickweed. A few other ingredients later and I was heading home, en route relieving a mahonia bush of a few of its bright yellow flowers, and was almost at my front door when I bumped into one of my favourite and most used city salads, wall bellflower. This plant absolutely thrives in urban locations, often growing in a conveniently elevated position, as its name suggests, out of a wall. With deliciously lush greenery and sweet purple flowers, I am able to pick this almost all year round. As I walked in the door, I picked up a sushi menu that had been pushed through the letterbox. Eureka! Who wants a salad when you can have sushi, or better still, wild sushi?

Wild sushi rolls with bellflowers, bittercress and salad burnet

They say that Scotland is a country of great innovations: the telephone, the steam engine, the deep-fried Mars bar, to name but a few. So it comes as no surprise that my friend Mark Williams, Scotland’s foremost authority on wild food, should come up with an idea bordering on genius! I’m often asked about the best way to cook or consume the foods we forage for and I always come back to the same thing – keep it simple. If it already has a great taste then why mess about with it or mask it under layers of other flavour? This is why Mark’s idea of using wild ingredients to make sushi provides such a superb platform for experiencing the delights of our wild larder, without the confusion or conflict of too many other ingredients. Below is a simple recipe for preparing sushi rice but I would not presume to tackle such a huge topic in just a few words and I’d suggest a good sushi cookbook would be more informative. With endless possibilities, it really is up to the individual to decide what to make and how best to approach it, but for my version I

created a selection of maki, small rice rolls, wrapped in sheets of nori seaweed, with a selection of my wild salads in the centre, seasoned with soy and Japanese horseradish, aka wasabi. For a native wasabi, consider using one of the more spicy relatives of cress or mustard, the best being a small coastal plant called scurvy grass.

3 cups (600g) shari (sushi rice), 120ml rice vinegar, 4–5 tbsp sugar, 4–5 tsp salt, nori seaweed sheets, assorted wild leaves and flowers

For the rice, cook the thoroughly washed shari in the same volume of water plus about 10–15 per cent extra. Bring it rapidly to the boil, stir it occasionally and then cover and cook it on a low heat for about 8 minutes. With a wooden spoon, carefully remove the rice, avoiding any that’s burnt or overcooked from the bottom of the pan and transfer it to a wide wooden or plastic dish to cool. Now mix the rice vinegar, sugar and salt, gently heating them before pouring onto the rice, carefully mixing it all together and then letting the rice cool again, but not in the fridge. That’s it – now grab your rolling mat, your nori and your wild salads and get rolling, perhaps having watched an online tutorial first.

26th December (Boxing Day). Roaming the streets of London

City life is a paradox, a choice (for most of us) to spend all our time in ridiculously close proximity to vast numbers of our fellow men and women, while at the same time constantly yearning to have more space, a little solitude and a greater sense of individuality. Today, however, London was empty, the streets were deserted, the roads almost unused and the usual level of background noise reduced to nothing more than the odd car and a bit of birdsong. I got the impression that despite the six million people resident in this massive city for the majority of the year, no one was actually a true Londoner anymore. They had all fled, back to their families in the suburbs, the countryside or abroad, as I would usually have done, too, but not this year. What a joy it was to walk down the road without the normal distractions, quietly appreciating the myriad street trees, usually passed in too much of a hurry for most people to even notice. My walk went like this: a pear tree, a cherry plum, a rowan, another cherry plum, a crab apple, a mystery tree, another pear, two hawthorns, a Turkish hazel, an avenue of common limes, a Judas tree, two black locust trees, a sweet chestnut, more hawthorn, another rowan. Then, turning a corner, a cockspur tree, which I had been unconsciously looking for and, unlike everything else I’d noticed – all of which would produce edible fruit, nuts or leaves next year – this was absolutely covered in seasonal decoration, dark red clumps of berries, to be precise.

Cockspur, sometimes called a cockspur thorn, is a non-native relative of our own hawthorn tree, similar in some respects but with oval leaves like those of a plum tree and protected all over by huge aggressive-looking spines. These thorns are an ancient hangover from a time when this tree would have needed to defend itself from large grazing animals, a feature still found on some of our native trees and bushes, most noticeably on sea buckthorn. Unlike almost every other edible tree in the capital, cockspur fruits very late and I have sometimes harvested the berries right at the end of January. Today I picked about a kilo, a task that took just a couple of minutes, each bunch containing thirty or forty individual berries. I wandered home to do some cooking, looking around as I walked . . . pear tree, crab apple, hawthorn, rowan, another pear, and on and on. My walk was ending, the year was, too, but foraging is a cyclical activity, the end of one season only heralds the beginning of another and they overlap so much that there is no time to think about endings, only new beginnings, renewed opportunities and the joy of whatever wild delights are coming next.

Cockspur jelly

1kg cockspur or hawthorn berries, juice of 2 lemons, brown or white sugar (1kg per litre of liquid)

I’m a huge fan of preserves but I generally enjoy eating them more than making them; the endless chopping, the use of masses of sugar and careful temperature controls are just not things that push my buttons. As a result, I’m always looking to create or simplify recipes as much as I can and this is the reason I prefer making jellies to jams, straining what I produce rather than carefully removing any unwanted parts; it’s just less work. Cockspur, like hawthorn, produces a delicious, quite stiff jelly, a little similar to a quince ‘cheese’, probably due to the high levels of pectin found in all of these.

Wash and remove the stalks from the cockspur or hawthorn berries, then, in a big pan, bring them to the boil with 500ml water and simmer gently for 45–60 minutes. Allow the mixture to cool and then strain it through muslin, wringing it out vigorously to get the maximum amount of liquid, then add the lemon juice and measure the volume before putting it into a clean pan. Add sugar at a 1:1 ratio, i.e. for every litre of liquid add a kilo of sugar, and bring to the boil, stirring continuously and keeping it at a rolling boil for 10 minutes until it reaches its ‘setting point’. Now decant the hot liquid into sterilized jars, being careful to leave any froth behind.